The coalition of Black and Red in Germany may be poised to assume unprecedented levels of debt for the purposes of defence and infrastructure development.

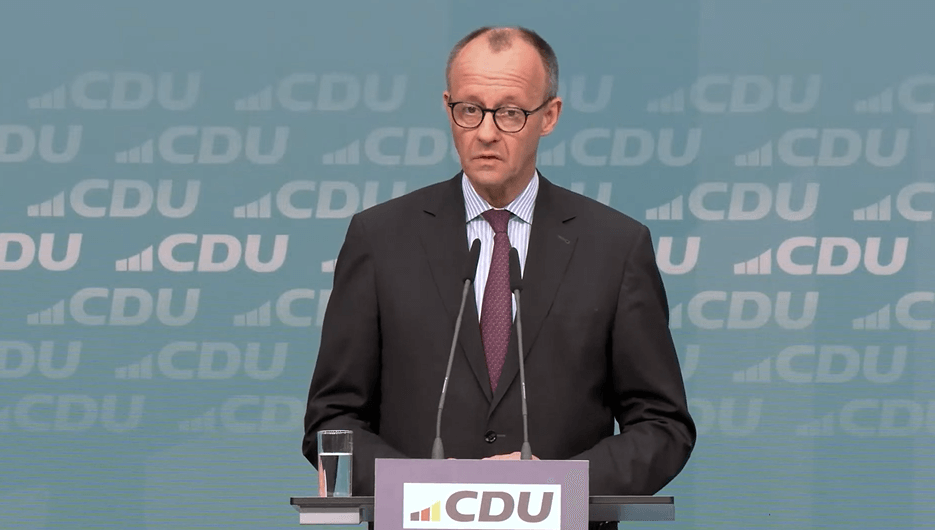

It is essential to avoid conveying the notion that the CDU is abandoning its core principles merely a week following the election. On Monday, party leader Friedrich Merz made a notable attempt to seize the discourse surrounding two substantial new debt allocations—one designated for defence and the other for infrastructure. “At this stage, we haven’t delved into the figures,” he remarked. Merz conveyed to his exploratory partners from the SPD the significance of a “shared recognition of the substantial necessity for budget consolidation.” Simultaneously, the CDU leader emphasised the significant urgency he perceives in light of the unfolding events in the USA. “It would be prudent for us to reach a consensus on this matter prior to the EU summit scheduled for Thursday.”

This “that” pertains to the inquiry regarding how Germany might substantially elevate its defence expenditure. The CDU is chiefly focused on augmenting the current special fund for the Bundeswehr or establishing a new one altogether. Both the SPD and the Greens, who currently enjoy a two-thirds majority in the Bundestag alongside the Union, are advocating for increased government expenditure on infrastructure. As reported by the Reuters news agency, a collective of economists, spearheaded by Saarland Finance Minister Jakob von Weizsäcker (SPD), has put forth a proposal for the establishment of a special fund amounting to 400 billion euros for the Bundeswehr, alongside an additional fund ranging from 400 to 500 billion euros dedicated to infrastructure development. Jakob von Weizsäcker’s superior, the Prime Minister of Saarland, Anke Rehlinger from the SPD, is a member of the SPD’s exploratory team.

The four authors behind the proposal—economists Clemens Fuest from the Ifo Institute, Michael Hüther of IW Cologne, Moritz Schularick from IfW, and Jens Südekum of the University of Düsseldorf—declined to provide any comments on specifics when approached. Nevertheless, one can employ approximate calculations to ascertain the means by which the 400 billion euros allocated for defence will be generated. In 2024, the defence budget amounted to 52 billion euros. In conjunction with the outlay from the inaugural special fund established in 2022, Germany has disclosed a total expenditure of approximately 91 billion euros to NATO, thereby fulfilling the obligation to allocate two percent of its economic output towards defence.

Inflation as a societal powder keg

Nonetheless, the dedicated fund of 100 billion euros is set to be exhausted by 2027, and a target exceeding three percent may be established at this year’s NATO summit, as indicated by Secretary General Mark Rutte. In a recent calculation, Monika Schnitzer, the chair of the Council of Experts, has estimated that the financial requirement for a new special defence fund for the years 2025 to 2029 will be approximately 300 billion euros, predicated on a quota of three percent. Should the target increase to 3.5 percent, it would translate to approximately 150 billion euros in annual defence expenditure for Germany—about 100 billion euros more than previously allocated.

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) crafted the blueprint for the special fund dedicated to infrastructure in June 2024. In a position paper released at that time, the association projected that an additional public investment of 400 billion euros would be necessary over the next decade. In terms of financing, it was also receptive to debt-financed special funds, which were frequently referenced by the SPD and the Greens throughout the election campaign. The BDI asserts that a sum of 158 billion euros is essential for enhancing transport routes, with a particular emphasis on rail infrastructure. The allocation stands at 101 billion euros for education, 56 billion euros aimed at boosting housing construction and energy-efficient renovations, and 41 billion euros dedicated to climate protection within industry and the enhancement of charging infrastructure. An additional 20 to 40 billion euros is required to lessen reliance on specific imports. The expenses associated with transforming the electricity grid, which have predominantly fallen on consumers to date, have yet to be considered, but the CDU/CSU and SPD are keen to address this issue. This may shed light on why the figure has shifted from 400 billion euros to a current discussion of 500 billion euros.

What might be the anticipated benefits and drawbacks to the economy stemming from the establishment of two funds of this magnitude? Oliver Holtemöller, an economic researcher at the Institute for Economic Research in Halle, identifies one primary concern: inflation. “Should we escalate national debt rapidly and extensively, we are likely to encounter genuine shortages.” What he implies is that there will be an insufficient number of construction workers, armaments factories, and craftsmen to manage an influx of expenditure. The outcome would be an increase in prices, as the government is willing to invest substantial sums. “It has become abundantly clear that inflation possesses the potential for social upheaval,” cautions Holtemöller. The ECB would subsequently need to increase interest rates, leading to higher costs for the state in refinancing its debt, which could create complications, particularly beyond Germany’s borders.

The impact of credit costs was minimal

The federal government presently finds itself in debt to the extent of 1.7 trillion euros, as reported by the Federal Ministry of Finance, or 1.86 trillion euros according to the Bundesbank, contingent upon the definition employed. The special loans suggested by the economists’ panel would consequently elevate the level by approximately fifty percent if fully utilised. The previous federal administration had projected an average interest rate of 2.53 percent in its preliminary budget for 2025. On Monday, this aligned nearly perfectly with the yield sought for ten-year government bonds. On Friday evening, it stood at just below 2.4 percent.

One cannot dismiss the possibility that the anticipated rise in credit requirements is already beginning to manifest its effects. So far, Germany has managed to secure borrowing at remarkably low rates, thanks to its strong credit rating. France and Italy find themselves in a position of greater indebtedness, necessitating the offering of higher interest coupons on their government bonds compared to Germany to successfully place them in the market. The administrations in Paris and Rome are presently contending with figures hovering around 3.2 and 3.5 percent, respectively.

During periods devoid of inflationary pressures and characterised by exceptionally lenient monetary policy, the significance of borrowing costs was minimal. That has already undergone a noticeable transformation. The costs associated with federal debt have surged nearly tenfold over the past two years, rising from a low of approximately four billion euros in 2021. In the year 2023, the figure stood at 37.7 billion euros. This year, the federal government’s interest expenditure is projected to be in the range of 33 to 34 billion euros.

Every additional tenth of interest swiftly escalates in cost

Statistics from the Federal Ministry of Finance reveal that over a trillion euros of the debt is financed on a long-term basis, utilising securities that mature after ten, 15, or even 30 years. However, a portion of it necessitates regular refinancing. Since 2020, the federal government has been compelled to borrow approximately 400 billion euros annually from the financial markets. Each incremental rise in interest swiftly escalates in cost. The standard borrowing associated with the debt brake, along with the two special funds currently under consideration, may elevate the federal government’s legacy burden by approximately one trillion euros. The federal government would be looking at an annual interest payment of nearly 68 billion euros, given the current financing rate on a staggering 2.7 trillion euros. With Italian expenses, this would near the 100 billion euro threshold.

It seems improbable that the EU budget regulations will pose a hindrance to Berlin’s ambitions. At the Munich Security Conference, Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the EU Commission, declared her intention to activate the “national escape clause” within the EU Stability Pact, aiming to exempt defence investments from its stipulations. The provision permits a member state to exceed the net spending trajectory established with the Commission for the forthcoming years. The application of the national escape clause hinges on the presence of “exceptional circumstances” that lie outside the control of the member state and substantially affect its public finances. The Commission views the Russian aggression towards Ukraine, particularly the anticipated erosion of US security guarantees, as a situation of exceptional significance.

Given that all defence investments are to be excluded, it is of little consequence from the EU’s standpoint whether they are funded via a special fund or through a reform of the debt brake. The Commission’s approval of a German infrastructure fund hinges on its intended purpose. Von der Leyen has declared “the utmost flexibility” in the enforcement of the pact. Nonetheless, the fund must establish a link to defence investments in a more comprehensive context. It is certainly feasible to consider investments in infrastructure such as roads, railway lines, bridges, or energy lines.

“Funds can likewise be invested in infrastructure.”

Von der Leyen is set to unveil her proposals to the EU heads of state and government this Thursday during their special summit in Brussels. Diplomatic sources indicate that a majority of nations are receptive to the proposal. It has been asserted that the requisite qualified majority will undoubtedly be secured. The Commission President is keen to unlock further resources from the EU budget through a process of repurposing. The contenders for this are, on one side, the EU structural and cohesion funds, and on the other, the unspent funds from the EU recovery fund. Both funds are designated, thus direct financing for armaments is not feasible. The Commission is, nonetheless, contemplating the provision of funding for infrastructure projects, including roads, railway lines, and energy lines. The primary beneficiaries would be the nations adjacent to Russia and Ukraine.

There are ongoing discussions regarding a dedicated facility to fund defence expenditures. This could be established either through specific contributions from member states or as an entirely new development bank. The latter would necessitate financial contributions from the involved states to ensure the bank achieves a top-tier rating. In both instances, one would anticipate that the United Kingdom and Norway, neither of which are members of the EU, would take part. On the other hand, nations like Hungary and Slovakia, which are against increased defence expenditure, would find themselves excluded. All these options would be arranged through intergovernmental agreements rather than through the EU, akin to the ESM crisis fund.

The lingering question is whether the special funds will enhance Germany’s productivity and, consequently, its growth prospects in the medium term, as recently posited by IfW President Moritz Schularick. The economist Holtemöller from IWH expresses a degree of scepticism. This is contingent upon a variety of factors. “Should defence expenditure be directed towards research and development, and should funds be allocated for new infrastructure, there is a potential for an increase in production capacity,” remarks Holtemöller.

It would present an entirely different narrative if the funds were allocated towards increasing troop numbers or addressing the issue of potholes. “Investment can likewise be directed towards infrastructure,” cautions the economist. The aftermath of the financial crisis, during which vast sums of euros were funnelled into economic stimulus initiatives, has left many feeling quite sceptical. In summary, Holtemöller overlooks the necessity of a political discourse regarding potential areas for financial savings concurrently. “The reality is that reductions are necessary to mitigate the anticipated rise in expenditure on health and pensions,” states Holtemöller. Up to this point, there has been an alarming lack of commentary from Berlin regarding this matter.

+ There are no comments

Add yours